"Helping Hands Make a Home"

From The Washington Post, Thursday, May 11, 1995, By Rajiv Chandrasekaran

Todd Hoban, by his own count, has helped build more than a hundred houses throughout Loudoun County, everything from rows of town houses to posh single-family units.

None of his many jobs gave the 26-year-old carpenter more pleasure than nailing together the wooden frame of a modest three-bedroom house in Leesburg on Saturday. For Hoban, the work in progress on South Wirt Street isn't going to be just any house.

"It'll be home," said Hoban as he carefully aligned a 2-by-4 for the front wall.

For the last two years, he, his wife and their two young children have been crammed into one bedroom of his wife's parents house in Herndon.

The Hobans have tried for months to buy their own house in Loudoun, one that is not too far from Todd Hoban's construction sites in Ashburn, because he doesn't drive. But with the average price of a town house in the county starting at nearly $150,000, the family, getting by on a carpenter's salary, found itself priced out of the market.

So earlier this year, Hoban's wife, Kimberly, decided to call the Loudoun chapter of Habitat for Humanity International, a nonprofit organization closely associated with former President Jimmy Carter that has built and renovated more than 34,000 houses for the poor in 33 nations. As it turned out, volunteers with Loudoun's chapter, which is two years old, were planning to build their first house in the county and were in search of a family in need of an affordable place to live.

Habitat volunteers have constructed many low-priced houses in the metropolitan area in recent years, including several in Southeast Washington and Fairfax County. But they say it's often in the region's outer suburbs, with their skyrocketing land prices, that people have the most trouble finding affordable housing.

"The single biggest obstacle in Loudoun is land," said Robert B. Pinkall, president of the Loudoun chapter. "There are dollar bills on every square foot."

Unlike Habitat groups in the District, which have found it fairly easy to acquire lots for their projects, finding a plot in Loudoun took two years of searching and fund-raising, Pinkall said.

Finally, after activities ranging from lemonade sales to a silent auction, the group was able to scrape together the $35,000 needed to buy a 5,000 square-foot lot in Leesburg earlier this year. It broke ground on the project April 1 and hopes to have the Hobans moved in by July 4.

"We're hoping to give them independence from substandard housing on the 4th," said Sandra Couch, a Herndon architect who is heading the building effort. The Hobans were selected from 20 low-income families who applied to buy the house.

Although many of their construction supplies, including lumber and insulation, have been donated, Pinkall estimated the finished house will cost $75,000.

The house will be sold at cost to the Hobans, who will make a 1 percent down payment and get a 30-year, interest-free loan. That money will be used to help pay for the organization's next housing project.

"We're hoping for six (houses) in '96," said Jeff Jenkins, a Leesburg home builder who also is supervising construction. "Right now, we're trying to find our second lot."

The Hobans' house won't be a mansion, Jenkins said, but neighbors will not have an eyesore on their hands either. The one-floor dwelling will have 1 1/2 bathrooms, a vaulted ceiling in the living room and a front porch. When complete, it will be "ready for move-in," with carpeting, fixtures and kitchen appliances, he said.

Pinkall said Habitat's home building efforts help a group of people neglected by Loudoun County's affordable-housing program, which requires large builders to sell 12.5 percent of their unites below market value. That program is targeted at people who make 30 percent to 70 percent of the region's $62,700 median income, although county planners said that most people in the program have an income of more than 50 percent of the median.

Habitat homes are designed for those who make less than half of the median income, including government employees, construction workers and others in Loudoun's growing service industry who commute from the Winchester area and parst of West Virginia.

"We're trying to help people live and work in the same place," Pinkall said.

Pinkall said he expects county assessors to value the house at nearly $125,000 when it's completed, a price tag out of reach of the Hobans, who will have to sign an agreement preventing them from selling the house at a profit for 15 years.

The reason the sale price will be so low is due to one factor, Habitat leaders said: volunteer labor.

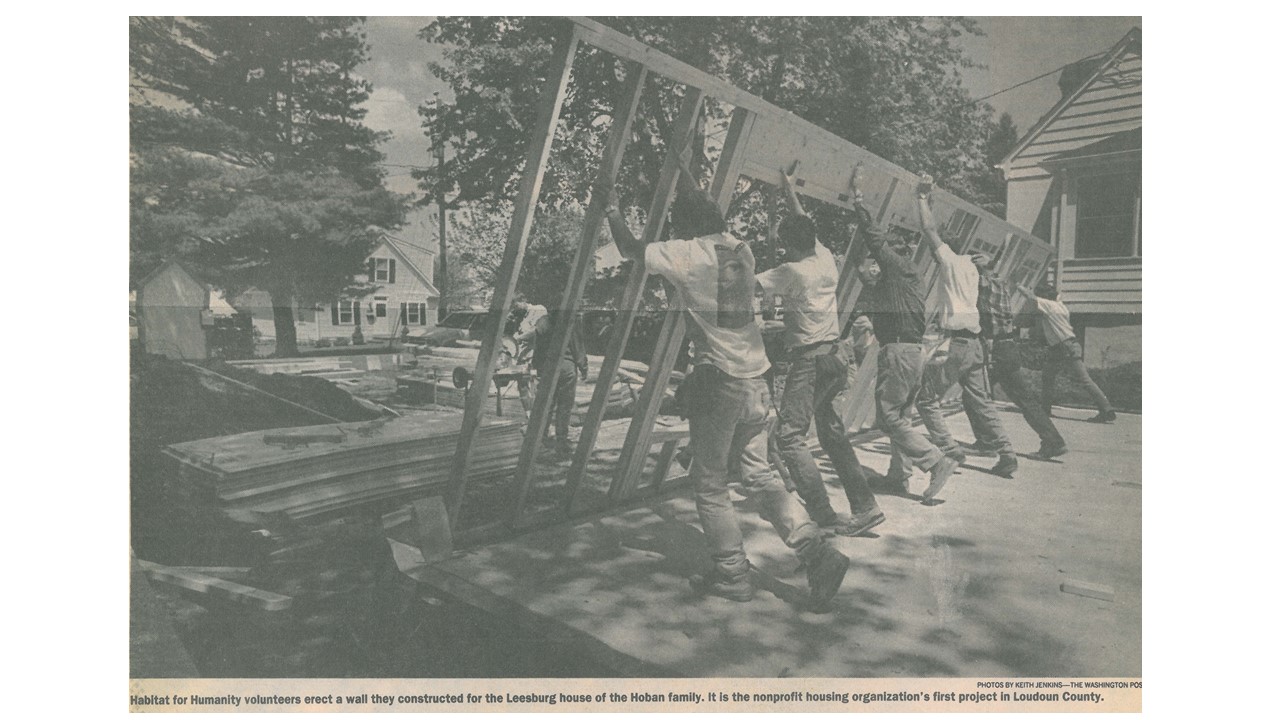

On Saturday, 20 volunteers, from computer technicians to professional home builders, strapped on tool belts and were doing everything from sawing wood to raising walls. Over the course of the project, much of the group's labor also will come from several local churches the group has formed "covenants" with, Jenkins said.

"It's a wonderful way to give something back to the community," said Frank Hinckle, a service representative in Virginia Power's Leesburg office, which supplied five volunteers last week.

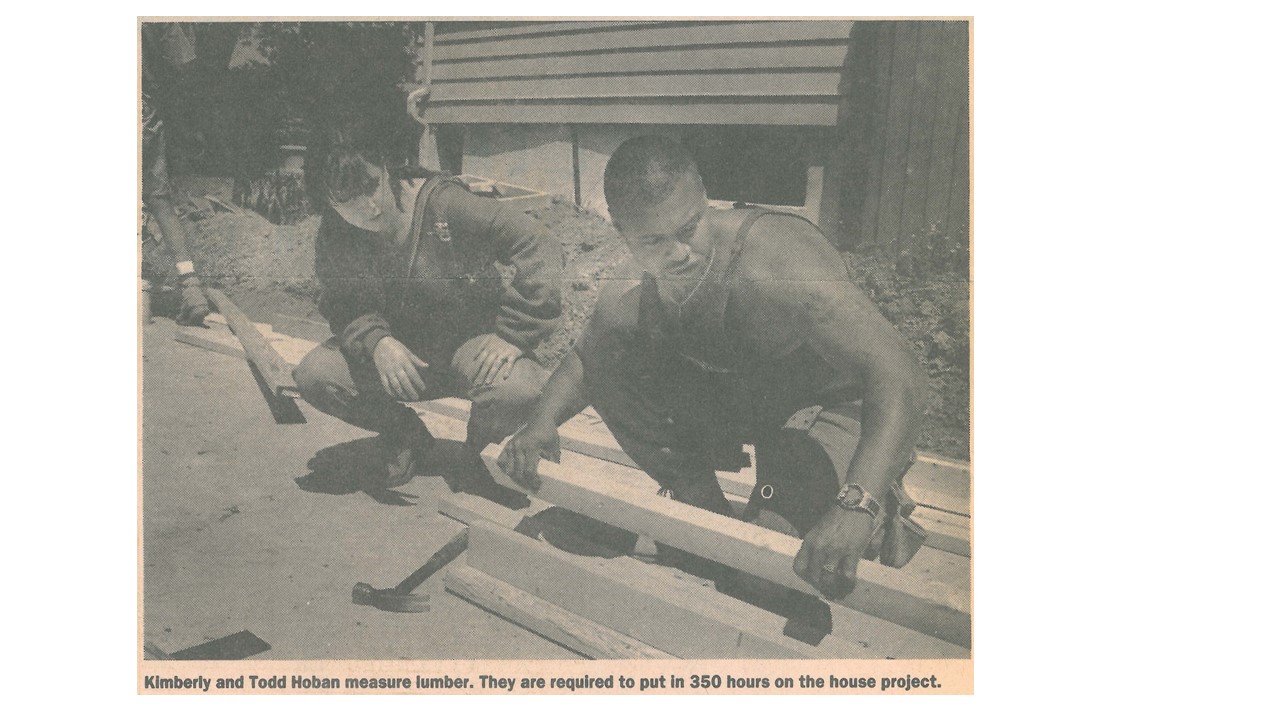

The Hobans also must provide their share of sweat equity. In addition to mandating that new residents come from substandard housing and have an income of less than half the county's median income, habitat requires them to work 350 hours on the house.

The couple has done everything from haul lumber to make precise fittings based on architectural drawings. Last week, as the first wall frame was being erected, Todd Hoban whacked in the first nail to hold it up.

At that moment, Kimberly Hoban, 19, dropped what she was doing and scurried up a dirt pile to capture the moment on film. She's planning on making a collage with snapshots and the blueprints - the first piece of art in the new house.